Understanding Diastasis Rectus Abdominus (DRA)

By Tiffaney Marlow, Reg. PT

The female body undergoes dramatic changes during pregnancy as hormones relax the ligamentous structures of the pelvis and most noticeably the tissues of our stomach stretch to accommodate a child growing inside of us. A common concern for many new mothers has been dubbed the “mummy tummy” or a diastasis rectus abdominus (DRA). Mainstream media, personal trainers and fad exercise programs often claim they have the solution to “flatten your stomach” again. The truth is research about DRA is very limited. The prevalence, risk factors and treatment approaches for DRA have been poorly investigated. However, as we learn more about trunk stability and the muscles that shape our core we begin to understand more about DRA and how to address it.

What is DRA?

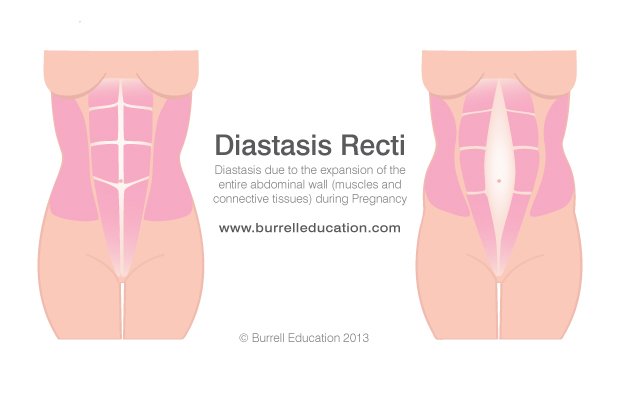

DRA occurs when the connective tissue, known as the linea alba, between the rectus abdominis or “six pack” muscles stretches and thins. DRA is measured clinically by the inter-recti distance (measurement between the two normal abdominal muscles) above, at and below the level of the umbilicus (belly button)(Sperstad et al, 2016). A pathological DRA is diagnosed as 4.5 cm or two fingers width of separation at any one of these loctions (Super et al, 2016).

Recent research found the prevalence of DRA at 21 weeks gestation, 6 weeks, 2 and 12 months postpartum were 33.1%, 60%, 45.4%and 32.6% respectively in a cohort of 300 first mothers (Sperstad et al,2016).The most spontaneous healing is thought to occur within the first 8 weeks postpartum , after which recovery often plateaus (Coldron et al, 2008). What does this mean for our patients who continue to have a pathological DRA after 8 weeks ? To better understand the effects of DRA we must understand how our functional core works.

What is a functional core ?

The core is so much more than just our stomach muscles that we target with sit ups and ab excercises. The core is actually 4 different groups of muscles and their respective fascia that work together to create a dynamic abdominal canister that provides support and stability to the pelvis, thoracic and lumbar spine (Lee et al, 2008). These muscles include:

Transversus abdominus (TA), horizontally oriented muscle which wraps around the abdomen like a corset.

Multifidus (MLFT), a large muscle located in the lower back

Pelvic floor muscles (PFM): a series of muscles that control continence, support pelvic organs and provide pelvic stability located at the bottom of the pelvis

Diaphragm (Dia): a dome shaped muscle that uses negative pressure in the thorax to pull air into the lungs.

The research has shown that the TA, PFM, MLFT work synergistically and in anticipation of movement or exercises that may challenge the core (Hodges et al, 2007). These muscles reflexively pre-contract in response to various loading of the limbs and both anticipated and unanticipated perturbations ( Hodges et al, 2007). Any disruption to the abdominal canister may lead to a failure in the system leading to incontinence, lumbopelvic pain and breathing disorders (Lee at al, 2008).

DRA disrupts the myofascial tension in the abdominal canister,. The stretching of the linea alba changes the fascial tension in the core and may limit the ability to dynamically stabilize the lumbar and pelvic girdle. So how do we restore stability of the abdominal canister?

Treating DRA

There has been limited research regarding treatment for DRA. Most intervention to date have included: exercise programs focus on engaging the abdominal muscles, postural education and use of external devices to support the abdomen.

There is some evidence that abdominal exercises during the antenatal period may reduce the risk for DRA postpartum for every 1 in 3 women (Benjamin et al, 2014). Hypothesis for this finding is that exercise maintains tone and strength of the abdominal muscles. Improved awareness of the inner core unit reduces stress on the linea alba and therefore reduces risk of DRA.

Benjamin et al (2014) also found that exercise focused on postural control and engaging the inner core unit (transversus abdominus) may also play a role in reducing DRA in the postpartum period. Improved strength, appropriate timing of inner core unit activation protects the linea alba and allows for more efficient load transfer through the abdominal canister. This not only may reduce DRA but allows women in the postpartum period to return to their activities faster.

Most exercise programs focus on trying to decrease the, inter-recti distance ( distance between the abdominal muscles). However, a recent observational study by Lee and Hodges (2016) found that a regular abdominal curl up exercise, although it decreases the inter-recti distance, distorts the linea alba. This means there is a loss of the myofascial tension needed in the abdominal canister. With a pre-contraction of the transverus abdominus muscle, although the inter- recti distance was unchanged, tension in the linea alba was maintained during the curl up task (Lee and Hodges, 2016). The early stages of this research challenge our prior treatment goals.

Some studies have included abdominal binders or wraps in conjunction with abdominal exercises recruiting the inner core (Benjamin et al, 2014). External supports are thought to mimic the abdominal muscles, provide support to the lumbopelvic region and give biofeedback to the inner core. The evidence for these devices is limited and inconclusive so further research is needed in this field (Benjamin et al, 2014).

Conclusion

In conclusion, much work is needed to fully understand diastasis rectus abdominus and how best to treat it. As a loss of fascial integrity in the abdominal canister, DRA disrupts the myofascial tension created by the core unit. Addressing postural re-education, lumbopelvic alignment and inner core stregthening and timing appears to minimize DRA and improve function. For more information about DRA and how to properly engage your inner core unit book an appointment with one of our pelvic physiotherapists today.

References

Coldron Y, Stokes M J, Newham D J, Cook K. 2008. Postpartum characteristics of rectus absominis on ultrasound imaging. Manual Therapy. epub

Hodges P., Sapsford R., Pengel L. 2007. Postural and respiratory functions of the pelvic floor muscles. 26(3):362-371

Lee D, LeeLJ, McLaughlin L. 2008. Stability, continence and breathing – The role of fascia in both function and dysfunction and the potential consequences following pregnancy and delivery. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 12, 333-348

Benjamin D. R., van de Water A.T.M., Peiris C.L. 2014. Effects of exercise on diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle in the antenatal periods: a systamatic review. 100(1)

Sperstad J.B., Tennfjord M.K., Hilde G., Elstrom- Engh M., Bo K. 2016. Diastasis recti abdominis during pregnancy and 12 months after childbirth: prevalence, risk factors and report af lumbopelvic pain. 50(17) 1092-6

Lee D and Hodges P. (2016) Behavior of the Linea Alba During a Curl-up Task in Diastasis Rectus Absominis: v An Observational Study. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 4(7) 580-589

www.burrelleducation.com